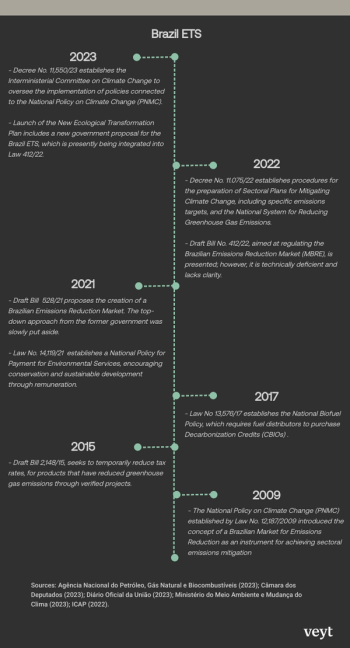

It has been 14 years since Brazil’s landmark National Policy on Climate Change (PNMC, or Law 12.187), which introduced the concept of a Brazilian market for emissions permits as an instrument for climate change mitigation, passed under current president Lula Da Silva’s previous presidency. During this time, the Brazilian Congress has seen several legislative proposals involving market-based emission reduction policies (see Figure 1), but none have included a detailed plan for an emission trading system (ETS) with permits/allowances and other attributes featured by active carbon markets in other jurisdictions such as the EU, North America, South Korea, or China. As of this year, however, an ETS bill supported by the Lula administration and the country’s main industry federation is making its way through Brazil’s legislature.

Figure 1 – Brazil ETS Regulatory Framework Timeline

The Federal Senate (upper house) initiated a proposal for an ETS in the form of “Draft Law 412/2022” last year – this year, the Lula administration launched a New Ecological Transformation Plan that included a proposal for an ETS (SBCE in Portuguese, for Sistema Brasileiro de Comércio de Emissions). The Federal Senate has incorporated the SBCE into Draft Law 412/2022, making that bill more likely to pass than any other attempt at ETS legislation Brazil’s Congress has seen so far, given that it has support from both the executive and legislative branches. It also has support from much of the country’s business community: before the Lula administration announced its final proposal for the SBCE in July, Brazil’s National Confederation of Industry (CNI) had presented a proposal for a regulated national carbon market to the government. This industry proposal included elements – such as a greenhouse gas emissions monitoring program and national allocation plan – that then made their way into the administration’s SBCE, and thus also into Draft bill 412/2022.

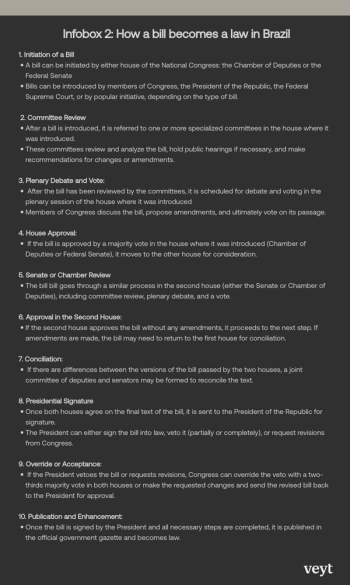

On 21 August, the environment committee of Brazil’s senate (upper house) approved amendments “based on the president’s proposal in the form of a substitute to 412/2022,” meaning lawmakers changed the original draft bill text to incorporate the SBCE components and several other amendments for a more robust Brazilian ETS plan. That revised bill was set to be debated and voted on by the Senate in September (see Infobox 2, step 2), with observers expecting it to pass and thus go to a vote in Brazil’s lower house called the Chamber of Deputies.

This was all assumed to happen rather quickly, given the aforementioned support from both executive and legislative branches and from the industry federation. In fact, the government had announced it expected the bill to pass before or during COP28, the annual global climate summit held in December this year.

Throughout September, however, legislators have delayed Senate votes on the bill, citing the need to review new amendments – this means it continues to be “stuck” at Step 3 of Brazil’s legislative process (see Infobox 2), making it very unlikely that the country’s climate negotiators will show up to COP28 in December representing a government that has just enacted a law creating a national carbon market.

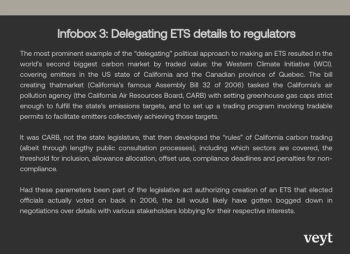

Like many pieces of legislation that create a policy involving specific targets and compliance procedures, the text of bill 412/22 sets up institutions necessary to govern the ETS rather than spelling out exact emission trading parameters in the law itself. For programs as complex as a carbon market, elected officials typically delegate the actual setting of emission caps and determination of e.g. offset use quotas or reporting requirements and compliance timelines to relevant ministries or other expert bodies, see Infobox 3. This speeds up the passage of the legislation, as lawmakers do not get bogged down by decisions that could favor one constituency over another – rather, they punt those to agencies staffed by experts, not elected officials.

The Brazilian Senate’s bill 412/2023 indeed first and foremost sets up institutions to implement the national ETS. It creates

However, the draft bill goes beyond merely creating institutions – since it is based in the original 2009 National Climate Change Policy, it sets some definitions and parameters directly because those were mentioned in that law. For instance, Draft Bill 412/2022 specifically sets the inclusion threshold for compliance entities at 25,000 tonnes CO2e per year, with a reporting threshold of 10,000 tonnes per year. This means sources that emit more than 25,000 tonnes per year are “covered entities” subject to an emissions limit under the ETS and therefore required to surrender allowances for their emissions. Sources emitting >10,000 tonnes per year must submit emissions inventories, as they could grow to become covered entities. The same inclusion/reporting threshold was used in the WCI (see Infobox 3).

Setting an inclusion threshold in the law determines to a large extent the controversial question of which sectors will be covered by the program’s cap. That in turn makes for more lobbying of the legislators voting on the bill, as stakeholders from various sectors seek to secure themselves advantages vis a vis other players’ interests.

In Brazil, the major player in this regard is the country’s influential agricultural lobby, whose goal is to ensure that the agriculture sector remains outside of the ETS. Given that annual emissions can only be reliably measured from large stationary sources like power plants and factories (not individual vehicles, farms and ranches, or forests), stating in the law that entities emitting more than 25,000 tonnes per year are regulated already implies that Brazil’s SBCE will cover the power and industry sectors. Indeed, analysis of Brazil’s economy suggests the affected sources would be primarily oil and gas companies, as well as producers/processors of steel, cement, and aluminum – 4,000 to 5,000 companies instalations would be affected.

Brazil’s powerful agricultural lobby seeks to ensure that the bill not only implies an SBCE covering only power and industry, but that it explicitly excludes their sector from greenhouse gas regulation. The most recent delay in voting was indeed primarily due to the influence of agriculture sector interests: one of the many new amendments proposed to Draft Law 412/2022 in September would explicitly remove primary agricultural production from the list of greenhouse gas sources subject to a compliance obligation. Indirect emissions from inputs or raw materials in agriculture would also not be covered according to this text, ensuring that Brazilian farmers and ranchers would not be subject to their country’s carbon market. Senators who are part of Brazil’s Parliamentary Front for Agriculture are the ones calling for more discussion before voting, as they wish to lock in their constituents’ exemption from carbon caps.

In other jurisdictions, the role of agriculture sector emitters would not be a dealbreaker for the progress of ETS legislation. In most industrialized countries, agriculture accounts for less than 20% of national greenhouse gas emissions and only a small share of GDP. Brazil’s emission profile, however, is somewhat unique among countries with its level of industrialization: in addition to significant emissions from non-rainforest-related sources (see Infobox 1), the vast majority of its contribution to climate change comes from land use change – including destruction of the Amazon Rainforest – and agriculture. The sectors in which large stationary sources operate (that would be covered by the SBCE) account for less than ¼ of the country’s greenhouse gas output, whereas agriculture and the “forestry and land use” sectors account for the rest, see Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Brazil Emissions Profile

For comparison, the EU ETS’s 1.4 billion tonne cap represented 38% of Europe’s emissions in 2022. China’s ETS covers only emissions from its power sector (about 4.5 billion tonnes), but that accounts for over 40% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Brazil’s farmers and ranchers thus have reason to be concerned: given how much their sector contributes to the country’s overall emissions, an ETS that does not cover them is arguably ineffective as a policy tool.

Moreover, the original PNMC from 2009 (in which Draft Law 412/2022 finds its legal basis) mentions specific sectors. Those are: energy, urban public transportation (cargo and passengers), manufacturing, consumer goods, chemicals production, pulp and paper production, mining, construction, health services, and agriculture. Ag interests thus find themselves drawing out discussions on the SBCE (holding up votes and passage to the next step of the legislative process) until their exemption from coverage is clearly secured in the bill text. They do not want the decision of which sectors to include being delegated to unelected expert bodies (whom they cannot lobby), as those bodies might seek to include the agriculture sector to make the SBCE more effective in reducing Brazil’s total emissions.

The government has explicitly stated that its ETS plan is not intended to alter existing carbon credit arrangements of Brazilian players in the voluntary carbon market, except to define the legal nature of credits, their taxation, and regulation of projects in indigenous areas or locations involving public land.

The bill leaves room for credits currently being transacted on the voluntary market to instead offset the emissions of Brazilian entities covered by the SBCE – new amendments favor nature-based projects that by definition take place outside the power and industry sectors. Credits would then be compliance units available to emitters: offsets those emitters can surrender in lieu of allowances to cover their greenhouse gas output.

The text of Draft Bill 412/2022 mentions offset use, but does not specify a limit or percentage – other ETS allow emitters to cover their compliance obligation with offsets only to a certain extent (in California, that percentage is 4 for emissions in 2021-2025), but the bill delegates setting such limits to the SBCE’s Management Committee. What that committee decides will in turn affect demand for offsets and therefore how many Brazilian credits remain available to other (voluntary market) buyers: if emitters covered by the SBCE are allowed to account for a large portion of their compliance with offsets, there will be higher demand for units from Brazilian projects – this will raise their price.

Credits from Brazilian projects currently involved in the voluntary market can also be sold to other countries as an Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. However as per the text of Draft Law 412/2022, these credits will need to be registered as “Certification of Verified Reduction or Removal of Emissions (RVE)” in the SBCE Central Registry.That way, the country can keep track of the amount of mitigation going toward fulfilling its own Paris Agreement target vs. mitigation other countries can count toward their target after buying from Brazil.

If Draft Law 412/2022 passes the Senate, it will be sent to Brazil’s lower house, the Chamber of Deputies – see Infobox 2. If this happens soon, the law could enter into force either this year or in 2024 – the government is keen to have it approved before COP28.

Entering into force, however, does not constitute operationalization of a Brazilian carbon market. Even with rapid approval in Congress, setting up the regulatory bodies the bill creates will take time – as will determining the cap and creating the rules of carbon trading specific to the program such as offset use limits and compliance timelines. Several outstanding issues remain to be decided, for example the legal classification of compliance units: it remains unclear whether they will be categorized as financial assets or commodities. Presently, credits from the voluntary market are classified as intangible assets in Brazil. Even the body responsible for this matter is still a subject of debate, with banks advocating for the Central Bank to assume responsibility vs. Brazil’s Securities and Exchange Commission (Comissão de Valores Mobiliários or CVM).

Despite all this, the Lula administration expects regulatory bodies to draft the SBCE rules within 12 months of the legislation entering into force, although it has admitted it could take twice that long. Covered emitters would then undergo a two-year “monitoring-only” period during which facilities are required to submit reports on emissions reductions and removals. Emission reduction obligations would only come into effect after this period.

Regulators, however, hope to have the market up and running by COP30, as that session of the UN’s annual climate summits is slated to take place in Belém, Pará (the heart of the Amazon Rainforest) in 2025.

Specialising in data, analysis, and insights for all significant low-carbon markets and renewable energy.